09195469370

shavandpublication@gmail.com

info@shavandpub.ir

نشر شَوَند

فلسفه، هنر، ادبیات ...

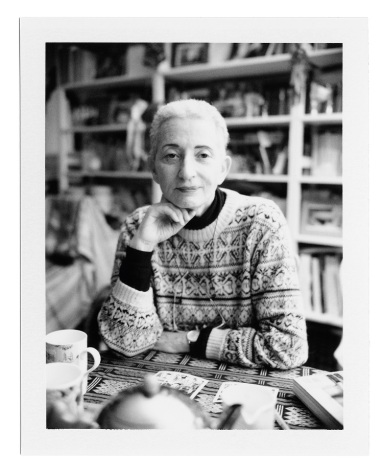

Living the Strangeness

Hélène Cixous, the great French writer, feminist, poet and philosopher was born in 5 June 1937 at Oran city, Algeria, of a Spanish-French Jewish father and German-Jewish mother. Cixous earned her French doctorat ès lettres in 1968 with her critical treatise on the works of James Joyce and next year she published her first work of fiction, Dedans (translated into English as Inside) and other fascinating works, by which she turned to a steadfast writer. She soon befriended with the leader philosopher, Jacque Derrida who referred to her as the greatest living writer and poet in contemporary French. Some of her works are The Laugh of the Medusa (1976), Portrait of Dora (1979), The Newly Born Woman (1986), Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing (1993), and about forty other books and nearly one hundred articles.

At eighteen she left Algeria in 1955, making her way to London for an educational period, and then headed for the recherché in university of Paris. In this way, she spent many years as a Jewish woman (or as she says, Jewoman) and a stranger without a certain original fatherland or decided nationality.[1] It is not wrong to say that mentioned hybridity, supra-nationality, homelessness and nomadism, whether as the personal life or in language, are the most important and permanent factors of Cixous ‘s thought. She denies all ethnic and tribal connections and their meanings, and declares that, “For me, being a woman, that has a meaning; it’s even the primary meaning” (Cixous, 2008, 137). As a hybrid woman who chose to leave her motherland and live multi nationalities, she would say that the philosophical condition of belonging to nowhere or being everywhere is a prerequisite of creativity which is the source of generation of the ‘passions of words’, or some kind of free, rhythmic and homeless expression which is completely necessary to releasing lingual energies, as well as, denying the male-oriented structures of language and thought.

In her political strategy of writing, Cixous tries to approach this nomadic self-defeating situation, thereby combines the imaginary activities, theory, feminist criticism, etc. by erasing the old-fashioned boundaries between them as interwoven realms. In addition, she attempts to attain a sort of language that as will be clear, can be realized through bodily experiences which the dominant masculine discourse mostly rejects them. Because of this new poetic style, Derrida is fully right to name Cixous as a thoughtful philosopher-poet, especially because her works are some counsels or meditations on the poetic and theoretical style or better, experimentations in the potentials of text and language, some kind of theory of writing or writing on writing through philosophy.[2] Her writings in which she thinks by fictions and non-argumentative words, are questions about the limits of the thinkable, aiming at revealing the unseen and unthinkable aspects of reality; in her view, this defense of freedom in writing would be possible only through interrogating the conservative styles. For example, in 1974, Cixous writes First Names of No One in which through rereading the works of writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, Freud, and … she is looking for an “elsewhere” to free the human subject from exchange relations in order to experience the ‘life without limits’ by reversing the usual economy of desire that always condemns women or men to mechanical western communication. As Julia Dobson states, ‘Cixous ‘s work, articulated in these poetic and polemical texts, strove to redefine the relationship between female subjectivity and language, through a reclamation of writing, a writing that was inextricably linked to the libidinal economy of writing subject … which centered around the concepts of ‘writing the body’ ’(Dobson, 2001, 7).

As far as the general feminism (as a social-political movement) is concerned, Cixous is not at all sympathetic toward the current prevailing feminist goals, and devotes herself to finding new unfailing directions for women ‘s freedom that is far from being influenced by temporal sociological movements. At the same time, as a post-modern philosopher, Cixous is one of the main founders of ‘feminine writing’ (écriture féminine), a textual style which allows us to be free from the constraints of Logocentrism and phallocentrism that are rooted in our world and language, and pave the way for the emergence of what we can call the female de-construction.[3] In her opinion, one of the typical examples of this type of writing can be found in poetry; for many of écriture féminine philosophers, poetry is the best language that could be feminine. In fact, unlike masculine language, the poetic female language is something like a broken and fragmented way of expression which is not based on logical rationality or theorism.[4] Contrary to the rational language which is limited to grammatical rules, our question here is, if the feminine writing has the power of thinking the unthinkable? What are the elements of female-deconstruction, and finally can we regard the feminine as the “other” of the masculine history of metaphysics?

Binary Oppositions

In the very early seventies, at the height of her groundbreaking ideas, Cixous paid special attention to the current issue of sexist tendencies correlated with the standard language and thought, as well as their dependence on the sexual dualism of reality. Regarding this value-based approach, she believes that the history of human thought and our seemingly advanced civilization, and also the annals of human language, both written by men, has always been based on so-called binary oppositions which actually divide reality into two distinct parts that are set off against each other. It is worth noting that Cixous in making such a philosophical proposition is largely indebted to great French philosopher, Jacque Derrida who through the conception of “Metaphysics of Presence” tries to criticize the time-honored tradition of western thought. He believes that all aspects of our language and traditions of philosophical thought have always been based on the assumption that we have a direct access to the meanings and significations, so then, they are based on the rejection of the unknown absent meanings. Therefore, speech as present signification has always been considered more valuable than writing which is thought to be a non-exist dimension. Derrida criticizes this logic of presence and believes that this vision leads to Logocentrism (centralizing of Logos, word, the present, reason, and on the other hands, rejection of the absent, the sensual, writing and …) against which he appeals to the process of deconstruction. “Cixous takes up Derrida’s point about the unequal distribution of power between the two terms”, but rather “focuses on gender divisions and argue that this power opposition also underpins social divisions, especially those between women and men” (Woodward, 2002, 36).

Focusing on the history of thought, Cixous addresses the issue of Derridaean criticism and supposes that male thought/language has always contained these oppositions and therefore leads maliciously to Logocentrism or phallocentrism (centralizing the symbolic power of masculinity by the power of phallus) or phallogocentrism which is a neologism coined by Derrida to refer the privileging of phallus-logos. Cixous does not separated these two dominant processes of masculine civilization and believes that “the critique of Logocentrism cannot be separated from a putting in question of phallocentrism” (Cixous cited in Sellers, 1994, 29). In the binary oppositions, there is a ceaseless judgment or estimation that prefers one part of dualism, a desire, a thought, an aspect over another part and puts the other on the inferior level, through which generates a hierarchical system that is absorbed in the textures and architectures of the world.

In 1975, in her important, exterminator text, ‘Sorties’ in the famous book, Newly born woman, she provides a detailed description of these oppositions made by phallocentrism/ Logocentrism and finally deals with the possibility of generating the facts based on the pattern of self/other. This new pattern serves as an alternative to a selfish human subject that is in some sense, the product of modernity. Firstly, she represents a comprehensive list of these oppositions in all fields of reality and lays emphasize on the position of women in such a tradition: ‘Where is she? Activity / passivity, Sun / Mon, Culture / Nature, Day / Night, Father / Mother, Head / Heart, Intelligible / Palpable, Logos / Pathos. Form, convex, step, advance, semen, progress. Matter, concave, ground – where steps are taken, holding – and dumping ground’ (Cixous, 1986, 63).

Cixous believes that these oppositions are something like a sweeping, cancerous stream that encompasses all philosophies, literary works, critical judgments and consecutive centuries of ‘representation and meditation’. These oppositions have become a priori requirements of the so-called emancipated thinking, and even the most sophisticated realms of human thoughts have used them to understand the world. Not only the public tradition, but also “philosophy is constructed on the premise of woman‘s abasement. Subordination of the feminine to the masculine order, which gives the appearance of being the condition for the machinery ‘s functioning” (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 40).

For Cixous the binary elements such as activity/passivity, sun/moon, culture/nature, and originates from the main opposition of man/woman, according to which men are equated with whatever is active, clear, powerful, superior or generally with positive facets, and on the other hand, women are identified with whatever is passive, inferior, dark (as Freud referred to women‘s sexuality as ‘dark continent’) or generally with negative aspects. As Woodward clarifies, “Those who criticize binary opposition would, ... argue that the opposing terms are differentially weighted so that one element in the dichotomy is more valued or powerful than the other”, and that is why Derrida believes that in any binary opposition the power works “in such a way that there is a necessary imbalance of power between the two terms” (Woodward, 2002, 36). That is why men are mostly regarded as ‘the self’ and the women as ‘the other’; man as the original, and woman as the marginal, secondary, the foreigner or stranger, just like a foreigner (maybe like Cixous herself) who enters a nationalist or racist society, and she will never be an insider, however deeply she is absorbed. This approach presents the white western man as a real original human being and rejects the other nationalities and races as the abject humans. Throughout history, all men have been in the position of this white man, while women have been rejected by a modern-like paradigm which actually makes the other more likely as a delinquent one. This is the situation Logocentrism has created; ‘… all these pairs of oppositions are couples. Does that mean something? Is the fact that Logocentrism subjects thought – all concepts, codes and values – to a binary system, related to “the” couple, man/woman?’ (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 38).

It seems that the interrelation of historical thought and binary oppositions is a fundamental reality that allows ideological systems to settle, seal and fix their principles and legitimacy; the ruling governors who are moving towards the statute and rationality which impose always the same stable pattern, not only to the subject’s mind and spirit of humans, but also to the world. However, Cixous puts this question that what will happen for Logocentrism, all great systems and current order of the world, if the foundation on which they built their houses collapses? What will happen to us if we eliminate and leave these dualisms, these stable structures? In order to be able to encounter with new facts and realities, we should leave behind the old ones. This could lead to the possibility of the emergence of new facts, new potentials, restless and living history, and to a renewal of the old structures. As Cixous states in Sorties, “So all the history, all the stories would be there to retell differently … the historic forces would and will change hands and change body – another thought which is yet unthinkable – will transform the functioning of all society” (Ibid, 40). But how does this process of postponement happen? Or better, what is Cixous‘s deconstructive method for dealing with the phallic distorting binary oppositions? Is there any way out of this deep-rooted melancholia, this infectious depression?

According to her, the male language which is based on phallocentric and erotic possessive desiring, often marginalizes women in society‘s borders and also turn them into the sexual objects. Furthermore, it may lead to what we can call the catatonic perception of the world. There must be a way out of these ontological and epistemological prisons, where women could be able to shout their freedom from the male type of tyranny once and for all; and even freedom of humankind from determined frozen realities. The force of their voices and their organs, should shake the frames of systems or the principles of those selfish men who cannot hear themselves and find a way out. It’s not only women’s voice, but also the voice of those foreigners who have always been rejected, and finally the voice of the unthinkable. It is only through the voice of the other that thought goes beyond the boundaries of representation and recognition. In fact, as Cixous writes in Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, “thinking is trying to think the unthinkable: thinking the thinkable is not worth the effort”[5] (Cixous, 1993, 38).

Anyway, Cixous tries to find a suitable way to dismantle through deconstruction (that she regards it as ‘the greatest ethical critical warning gesture of our time’ (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, xix)) the historical contexts and patriarchal peremptory language in order to reveal the new ways of expression. For this purpose, she uses numerous concepts, but the most important one is the idea of women’s writing.

Women’s Writing and the bodily language

In her works, Cixous is concerned with the open unexperienced forms of writing. In this respect, the practice of writing and the act of creation of the words, has a direct link to the sense of loss and mourning, in which there must be a sublimation-driven device to reduce the pains of lost objects. Writing serves as a means by which one can compensate and retain her/his deadly emotions, in a way that one can find some life-giving meanings in order to go on and communicating with the others. When we have nothing left but our own sensations, we find that writing is the real last resort which provides directions to start again everything. “Everything is lost except words. This is a child’s experience: words are our doors to all the other worlds. At a certain moment for the person who has lost everything, whether that is, moreover, a being or country, language becomes the country” (Ibid, xxvii). This concept of language might be regarded in Heideggerian sense[6], as a common/individual home, language as “the house of being”, a nameless free land or an infra-national country in the bosom of which there is a place for our own unlimited expansion. However, she tries to prioritize the act of writing over the oral speech, in a Derridaean tradition, by saying that “the indirectness, the obliquity of writing, the multiplicity – of layers of signifiers ect. – is almost excluded from the act of writing orally” (Cixous, 2008, xiv). By the way, the powers of writing could lead to the generation and formation of the motive forces which pave the way for the creation of new descriptions about our relationship with our body and others and subsequently, to the transformation and changing of our being in the world. Susan Sellers gives a sufficient description about Cixous‘s emphasis on writing as a way to invade the archaic mastery, “For Cixous, language is endemic to the repressive structures of thinking and narration we use to organize our lives. Since woman has figured within the socio-symbolic system only as the other of man, Cixous suggests that the inscription of women’s sexuality and history could recast the prevailing order” (Sellers, 1994, xxix).

Given the importance of writing mechanisms in defining the identity of human beings, it is understandable that for women who are considered out of all present and active dimension of society, language, or better, some sort of personal words as the feminine writing become a potential power to get rid of, to squash of the law of the father.[7] To begin with, as far as the concept of language is concerned, the symbolic grammatical male structures, embodied in the idea of law, always try to reject the other discourses, unknown syntaxes, and different unusual ways of wording, neologisms or linguistic creativity. This is the result of a once and for all distinction between truth and falsehood, meaningfulness and meaningless, formal and informal, speech and writing … through which the meaning in terms of philosophical discourse, would actually attain the Platonic sanctuary (the world of Forms and Ideas in which there is no change and uncertainty). In short, due to its unspectacular and fixed constructions, as well as due to the rejection of the differences or heretic styles of being and writing/speaking, the male worldview just happens and establishes in a tiresome state which repeats the determined principles, the said. In such a restrictive world, women’s feelings and passions which can make the language an aggressive entity, would become the ‘unthinkable’. On the contrary, one can argue that the language should be like a desiring event, by which women should go beyond this male language through their own progressive invention that is based on permanent desiring. For Cixous, the writing is a way to bring into play and to penetrate in the male discourses, in binary oppositions. She introduces this concept in her famous books The Newly Born Woman (1986) and The Laugh of the Medusa (1976) which is dedicated to Simone de Beauvoir. By creating the new styles that are not subject to dominant syntax rules, women can open up some new ways of thinking which allow them to be free in the experience of language as well as representing the reality. “If there is a somewhere else that can escape the infernal repetition, it lies in that direction, where it writes itself, where it dreams, where it invents new worlds” (Cixous, 1986, 72).

Women‘s writing has a deep unorganized connection with the free variegated voice of women. Feminine voice is a free and non-exclusive entity, a noise-induced permanent hearing that generates a displaced position, “Voice! A jet, - such a voice, and off I would go, I would live. I write. I am the echo of her voice her shadow-child, her lover … the voice opens my eyes, her light opens my mouth, make me cry out. And I am born from this” (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 50). To put in other words, female voice that has always been suppressed by Father’s ‘No’, needs to cry out for the infinity. It should be noted that, the female voice is not solely limited to the domain of women who try to overturn the symbolic organization, but the fact is that feminine spirit is the only way in which humans are able to change the male conventional points of view, especially when we recognize that due to the polyphonic characteristics, bodily rhythms and a sort of sentimentalism which are attributed to the pre-symbolic dimension of M/Other, they can change optimally their relationships with themselves, language, and the world. Hence, this writing is linked to deeper levels of meaning which derives from the body, where the writer can experience the words through and by her bodily encounters, inviting humans to take scrupulous responsibility for what they think about.

Therefore, one of the most evident features of the feminine writing is it’s connection with bodily dimensions and divergent sexual resonances in writing subject matter, which is an effective way to release the other languages. The grand narratives of linguistics, literature and philosophy have always considered language as an abstract, isolated and closed arena which has nothing to do with the physical body or writer ‘s weaknesses and symptoms, or yet regarded the works of art as something that are less linked to the author’s biography. In this respect, Cixous believes that it is not possible for language to function without the physical body that includes the emotional effects. As cixous declares in The Laugh of the Medusa, “By writing her self, woman will return to the body which has been more than confiscated from her, which has been turned into the uncanny stranger on display … Write your self. Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forth” (Cixous, 1976, 7). The first step is to perceive and to inject the different modes of female flesh, feelings and carnality into the sculpture, the status of writer subject. This particular rejection of long-standing dualism, the human body as opposed to mind, is also reflected in Cixous ‘s literary-linguistic style, as well as her playful using of the words and unveiling of their potentials; where the flesh of words (letters, the unusual forms of terms, changing syntaxes, …) can determine the meaning of signifiers. The aim of this foreign language, the one which she calls “body words”, is to enable us to extend our ability to understand the “out of fields” elements through a political action which can make a break with the male symbolization in a decisive sort of way: unique markings or notations, scrawling, writing in a sloppy manner against the rules of formal types or syntaxes, playing with the pronouns and the frameworks of male words, and any kind of interpolations or neologisms such as her polyphonic and synthetic ones which all are some non-configurable, non-writable possibilities to represent the female writing. For example, in Neutral (Neutre) in a poetry under the title of Holocaust, Cixous tries to bold the sexual differences in her text using some changeable female, male and plural articles, as follows,“épaisse peau de fumée orientée de bas en/haut le feu, la fumée…la ou les cendre(s)/pas de Vent/et de haut en bas, méconnue, la bouche” (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 7). Or this is, as Cixous states, what happens when for example instead of using one of the terms of Yes or No in respond to a related question, we replay it by saying the composition of Yes-No (say, neutral) or any other synthetic words, all of which will be possible just through the negative power of its seemingly meaningful patterns. This kind of circular, transitional writing, according to Cixous, is the very possibility of transformation, an open space which could be a springboard for destructive ideas or a proper movement for socio-cultural reformations.

Linking the unwritten, forgotten or repressed feelings with the language, the women‘s writing paves the way for doing experience due to new identities and human own bodies. That is why, for Cixous, women can write in white ink, through the process of effacing the peripheries. Cixous first of all equipped her style with a new unpredictable form of sexual difference, which can dismantle the sexual borderlines. As Sellers argues, “Cixousian writing does not name a he without a she… in other words, this writing is informed by the differential of sexual difference, the strange truths that it conveys… the between at work which escape classification; a between-two, which makes three and more; a betweentime which exceeds time” (Sellers, 1994, 214).

Apparently, the volatility and flexibility of this female style makes it look like poetry or poetic discourse. In spite of architecting some passages of her works as poetry, Cixous retains rhythmic and melodious tones of both poetic and theoretical works to avoid moldering in the dust of walled clichés.[8] This poetic spirit which acts like it deconstructs the magisterial language and releases the strength of non-syntactic potentials, is the internal part of female writing. That is why, in The Book of Promethea (1991), Cixous speaks of her faith in poetry and task of bridging the immeasurable distance between informal feelings and formal language. But what is the propulsion of poetry? It can be associated with the idea that poetry is the night dream of language; the poetic language originates from the unconsciousness. In this regard, in Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, Cixous describes the source of female/poetic writing as something dreamlike and imaginary, emphasizing the importance of our dreams as the main prerequisite of creative writing; resorting to the realm of subconscious, dreams, overnight experiences, ecstasies, raptures … . Dreams can provide powerful clues to one’s ontological state and can break the superficial shell of our-selves, hence, ‘we should write as we dream; we should even try and write, we should all do it for ourselves, it’s very healthy, because it’s the only place where we never lie. At night we don’t lie…” (Cixous, 1993, 198). In this regard, Poetry belongs to the dark realm of unconsciousness, beneath the kaleidoscope of realities or dreams, which most of its facets has been repressed by human subject’s masterful rationality. All these features, especially the fact that she wrote a book on poetic dimensions of the words, prove that there is a primordial, original relationship between writing and inner realm (internal language, rather than external, conventional one). The official language is always based on a conscious, attentive human subject who represents the superego or symbolic law/language and is fully aware that how to use the multiple syntaxes and grammars, while we should pay more attention to the internal realm of writing, such as unconsciousness forces which rapture the integrity of subject and reveal his hidden desires. ‘Writing (…) does not come from outside. On the contrary, it comes from deep inside. It comes from … the “nether realms”, the inferior realms (domains inferiors)’ (Ibid, 204).

Cixous tries to pose her theory of writing on two levels; on a non-theoretical level according to which there must be some kind of transparent framework as a support upon which any materials of act may be used in fashioning the words or concepts; and on a practical level which takes distance from presupposed stylish factors to free the latent possible divergences. Because of this second aspect, in spite of speaking about the female writing and the female practice of wording, she keeps herself away from concrete definition, or indeed, limiting its vast incalculable scope; in other words, she tries to provide just a personal example of it among many others, rather than determining one definite model for it. Cixous argues that the reason why we cannot and should not define this version of writing is that, if we do, we replicate and reiterate the same fault which is accomplished by male dominant style of language, which is nothing more that enclosing and dispatching the infinite possibilities of language and the world. According to The Laugh of Medusa, women’s writing is impossible to be defined as an action [cannot be summarized by one phrase or specific factors too] and it will remain impossible, for this action cannot be theorized, coded and enclosed; but this does not mean that it does not exist … (Cixous, 1981, 47).

This open situation in writing that many modern theorists don’t consider in their linguistic thoughts, is the very feature of female writing/language: “dispossession”, which means, first of all, removing any kind of properties from the subject of enunciation. In the last part of Sorties, Cixous notes that the female writing is the one that will destroy, through the operation of replacement, the established relations between self and the other; destructing all lingual fences and normalizing boundaries to achieve emancipation. Here we have many different instances in Cixous’s work for this figure, such as the very process of de-personalizing, divided subjects, the ability to open the self to the other subject ‘s worldviews, bisexual actors and so on. It is a movement from self to the other during a sort of intuitive identification, without the calculative causation latent in the argumentation or economical sharpness; as nobody, anonymous other who can release its powers facing the text or literature; a writer who does not occupy the position of established authors; and a reader who is not sure of finding definite meaning.[9] She refers to this new person in a final part of a text called First Names of No One, “these great destroyers are also great givers of strength, and of forms: through this shaking of the literary ground, those who crack it open pull off amazing effects, glimpses of ways out. How can we hold on to them? It is by moving onwards, beyond the known…” (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 33).

Another aspect of these characteristics which is also expressed by Marcel Mauss[10] in his famous anthropology in terms of meanings and functions of the gifts, is related to Cixous‘s earlier idea of male/female forms of economy. In her opinion, a distinction can be made between two primary types of economic behaviors in humans: men are always treated as possessors in the manner in which the supposed relationships meet the requirements of economy. Accordingly, gift-giving as a process of communication in male systems aims at stabilization and retention of the general economy (macroeconomics) and affirmation of an exchange value based on the logic of profit. On the contrary, regarding the women this situation is different, where they give the gifts without conventional human accountability or profit-driven reasons; conversely, their behavior are motivated by their desires and anxieties, which according to Mauss destruct the so-called insightful logic of general economy, and create residues or incidental expenses and lead to the surplus and excesses as non-calculative form of exchanges. Of course, Cixous believes, “there is no ‘free’ gift. You never give something for nothing. But all the difference lies in the why and how of the gift, in the values that the gesture on giving affirms, cause to circulate; in the type of profit the giver draws from the gift really and the use to which he or she puts it” (Ibid, 44). According to her philosophy, the normal male mechanism is the best and easiest way to make more money, status and power, by virtue of the property systems which are based on some kind of phallocentric narcissism with the concept of ‘return’. It is the way in which the parts of male society are structured or organized, which primarily refers to the influence and authority of law within male-oriented civilization. However, as Cixous states, it should be noted that, women fall in the beneficial relations in the same manner men do, yet this is not to say they experience totally the same things, but different aspects of things. In other words, women use the exchange-gift process in order to be happy, to create the possibility of emergence of non-profit human pleasures, and not just to ‘recover expenses’.

The overall concept of female writing is to be understood as a manifold open process, with many other aspects which will become clear in what follows, along with surveying some of the consequences of Cixous’s thought. In the following, we will argue that in what way her thought is linked with the idea of the female as the power of thinking the unthinkable.

Borderline Subject and New Identity

In describing or exercising the strategies of femininity, Cixous does not limit herself to the lingual elements of writing, and tries to pave the way for the emergence of different aspects of human creativity to trash the institutional structures of male hegemony: sexual difference and the bisexual subject as a substitute for the repressive policy that ruled over the women. Firstly, despite many of feminist movements that are led by social feminists who generally reject and ignore the gender/sexual differences, she introduces the sexual biological differences between the two sexes as a precondition for seeing the women on their own terms, yet for recognition of new ways of being such as being bisexual. This alternative as a political concept which is rooted in the affirmation of sexual differences will challenge in some way the mono-sexuality of the male discourse of psychoanalysis. Although it is not important to focus on and clarify what the biological body and anatomical organs can do as such, but “sexual difference is important in the role it plays in determining gender behavior, with its most capacity to uphold or challenge the existing order, rather than as anatomical difference per se” (Sellers, 1994, xxviii). Consequently, the issues of sexual orientation, strategies of sexuality and sexual experiences, are necessary to understand the perennial question of human non-symbolic possibilities as a way to discover and liberate our creativities and obtain new insights about the world.

We should remember that in addition to the dichotomies which all are the results of logocentrism, phallocentrism also leads to similar results: sexual primacy of phallic organ over the female, generating the impression of feeling danger for losing the male/symbolic organ in women, and creating the presupposition according to which women are different from and unequal to men sexually … Indeed, Cixous criticizes some of Freud’s sexualized or sexist reflections and challenges in The Laugh of Medusa the concept of castration anxiety in psychoanalysis. Cixous totally rejects Freud’s call for sexualization of medusa, and his psychoanalytic interpretations of sexual life of adult women in terms of hysteria or as ‘dark continent’, and tries to show that although Freud reveals the unconscious orientations, dimensions and prejudices of his patients, but remains surprisingly unaware of his own impervious judgments that mostly formalize his male discourse. In Portrait of Dura, Dura finally refuses to accept the burden of imperatives imposed by the law of Father, leaves the sessions of psychoanalysis and break off Freud’s therapy project. The main problem here arises from these assumptions in psychoanalysis, because of the very law that govern the process of desiring, the vision that is opposed to the free manifold flow of the libidinal stream. Furthermore, the psychoanalytic principles impose strong limitations and obligations upon women, designate their roles in advance, and in fact, determine their bitter fate once and for all, while as Cixous believes, there is no fate for women, nor a nature and a priori essence carved on the tombstone; conversely, there are sort of live restless structures which sometimes are frozen within the bounds of cultural-historical limitations (Cixous, 1981, 162). The last attempts to retrieve and restore the archaic frozen structures, as well as the endeavors to redefine female identity, herald a new image of femininity. A woman should even be released from the domination of semi-scientific disciplines such as psychoanalysis, and try to open up the ways of freedom in order to shatter and destroy the same historical limitations. Through elimination of the borders, by crossing the boundaries of identity, the women (humans) would be able to attend at different locations and substances [in both sexes]. Those who believe in borders will get into trouble and have to seek shelter from this holistic mixing. So, the woman becomes the symbol of anarchy, hence it can shakes the conventional “tableau of a general repression”.[11] In other words, the fear of sexual difference dismantles the whole symbolic and ordered structure of masculinity or modern Cartesian reason; just like as the realm that Freud calls the ‘dark continent’ can raid the symbolic dimension due to its darkness and unrecognizable murkiness and the nighttime.

Marginality of Otherness

From Cixous’s texts, we can conclude that women in general are the factors of positive chaos, and only through this characteristic they can shake the binary oppositions and male authority. All aspects of her philosophy, which encompass different areas, try to critique the status quo. As we have seen, the feminine writing, de-property, entering the female body in the text, sexual desire and … are some examples of this movement. Cixous is looking for a new understanding of the feminine without definition, whose architect is divergence. At the same time, she is very optimistic about possibility of changing the symbolic orders through this new female space, because as she says, “it is the in-between-us that keeps us open to the other, to otherness” (Cixous, 2008, 154). The major question here is how the ontological process of becoming women is linked to the supposition of woman as the marginality, and in what way it can convert itself into the other, by creating a permanent opportunity for women to save the alterity, without stopping the stream of otherness? We must examine how female space can pave the way to the supposition of woman as the marginal, and why this is important at all?

To begin with, acceptance of feminist demands for equality, should avoids falling into the traps of male procedures. Instead, in addition to trying to achieve their legal demands, women should grope a new switcher order and facilitate the formation of a dynamic structure. As Cixous believes, ‘women‘s liberation must be accompanied by the institution of a new socio-symbolic frame’ (Sellers, 1994, xxviii). But here lies the big danger: the risk of becoming this new order to a new construction that obeys the logic of masculinity, that is, consolidation, stability and centralization, rather than displacement, uncertainty and instability or in-centralization. If the new female order tries to occupy a position, it will settle itself in the same position that it was going to fight it. Avoiding this vicious dilemma is hazardous, a difficult deal that requires getting to the point of fluidity, self-destruction, and this is, in fact, a dangerous plague which latent in all political acts.

Going beyond our human borders provides human selves with more opportunity to find other patterns: the pattern of self/other, where an appropriate space is provided for the presence of the other within the self, a self-transparent subjectivity who is nothing but links with others. Cixous speaks “of femininity as keeping alive the other that is confided to her, that visits her, that she can love as other. The loving to be other, another, without its necessarily going the rout of abasing what is same, herself” (Cixous, cited in Sellers, 1994, 42). As we have seen above, the female as the alterity can flower only when female subject handles their being ‘out of joint’ and reaches a certain level of in-stabilized situation. This borderline situation has several aspects, one of which is a different distorted image of human subject, which is the first manifestation of female as marginality. In other words, one of the main results of Cixous’s debate is a divided and fragmentary human subject who is divided within itself into two parts. For example, we can think of the uncanny experience of pregnancy during which women prepare a sort of biological morals and even responsibility for living with the other (a not-yet-human). This is something more than one-dimensional subjectivity which is limited to the modern conception of self, so it occurs through the internalization of alterity as the process of becoming M/Other. This concept introduces a new existential paradigm which is possible only through existence of the mother, of the female. Cixous‘s conception of this new fragmentary subjectivity and multi-human -self is located at the heart of the ontological abyss within, thus works against the modern Cartesian subject. As she states, “pure I, identical to I-self, does not exist. I is always in difference. I is the open set of the trances of an I by definition changing, mobile, because living-speaking-thinking-dreaming. This truth should moreover make us prudent and modest in our judgements and our definitions. The difference is in us, in me, difference plays me …” (Ibid, xviii).

It is in very wriggle that we can find an open place, a room in ourselves. This new version of identity means that the human subject is essentially a relational creature who is formed by an ontological gap between the familiar (self) and the stranger (other), the two part of the one which transform each other through the multiplicity of the self. From this idea produced by deconstruction of the self, it follows that human subjects are not some coherent isolated entities that can be distinguished from others by virtue of their own borders. Accordingly, blurring the boundaries between me and others, indicates that the state of being different from and alien to ourselves, the quality of being self and the other is the essential element of human being. In other words, subject’s identity as a polyphonic voice is constituted not only by its self-affirmation but also by the strange forces that expose its existence and motivate it’s interaction with otherness. That is why our existence or, in Derridaean term, the signifier of our being, is fundamentally shaped by différance and postponement. This split subject is something like an experience of two in one, two sexes in one sex, a bisexual body, exactly what Cixous refers to, using the first letter of her name; the letter of H, as composed of two I (self) which are linked together by an inner line. This multivalent and polyphonic version of subjectivity becomes one of the main themes in Cixous’s thought, by which she can change the logic of self-other relationship. Accordingly, the deconstruction of the subject and language could be possible inasmuch as the Other comes to being; a female subject who can always emphasize on its otherness, and consistently maintain the foreign elements in itself.

Therefore, Woman/Other is not a normalized machine to be built after a model suitable for some social human beings, rather it’s an ontological tool which constantly runs away from becoming a paradigm, and dismantles the precast orders of prefabricated humans. This Woman/Other is solely actualized and comes to being through the female divergent identity who lives in the margins; the feminine as the precursor of otherness, something like the confirmation of difference. While most of men are looking to sustain their own well-established and delimited beings, what is meant by female subject is not an abstract, transcendental essence. Quite the contrary, it’s a permanent possibility to escape from essences and prior patterns. That is why, according to Cixous, the real emancipation will only be realized by those traits that women can release more than men. Many of these features can be traced in her works: deconstruction of binary oppositions, nomadism and homelessness as an anti-pattern against the paradigm of settling, de-possession and the surplus in macroeconomics, emphasizing on the physical and erotic charges, women’s writing as a dynamic factor to dismantle the monophonic structures and ultimately the feminine as something that is always on the margins, the sidelines of the symbolic, whose strange agency will get lost by entering into the realm of men: the female as the marginal. As Jacobus believes, “Cixous’ solution is to see woman as marginal, but not necessarily excluded from language. The woman is freer than the man … she has no responsibility for the norms; she can be more radical because she has an ironical position towards them. It does not cost her too much to reject norms that exclude her anyway. It is possible to write oneself through the norms, out of the concepts, the codes, to new freedom of the mind” (Jacobus, 1999, 9).

Considering the influence of Jacque Derrida and his main idea on Cixous‘s thought that “there is no outside-text”, it is not surprising to see that for her, most of these features materialize within the border of writing. Paradoxically, it seems that the Derridaean thesis is not radical enough to her, especially when we think of the main character of female writing which is nothing but a permanent process of going outside.[12] According to Cixous, however, women’s writing is nothing but writing for/of the other (other languages, other words), which is involved in being inside and outside at the same time, where the not-yet-author (someone who flees from the role of author) becomes an open combination of bodily aspects, sexual bars, irrationalities and outside forces, as well as texts that become the mixture of feelings and words.

She invites women to pave the way for divulging their existence out of imperial male world through writing the unthinkable, writing about the experiences that cannot be verbalized into the language through the conventional grammar and words, the ones by which they might discover the unseen aspects of the world and new ways of looking. This is one of the most important outcomes of the female as the strangeness: opening up the space for the emergence of the unseen, maximizing the ongoing unlimited possibilities of creating the new by virtue of granting the otherness. Escaping from any nature, is exactly what constitutes the nature: permanent displacement and exclusion of any stable identity. If the female is a whole, “it is a whole made up of parts that are wholes, not simple, partial objects but varied entirely, moving and boundless change, a cosmos where Eros never stops traveling, vast astral space” (Cixous, 1986, 44).

This boundless space is exactly what links the alterity to the “axis of indetermination” (a word that can refer to the situation of a volatile and elusive subjectivity realized by the female). In Cixous’s view, realizing this indeterminacy is an unenviable and cumbersome task that requires the self-denial and self-defeating. But how does this mechanism of indetermination work? This does not happen except through the process of self-critical abeyance which leads to the centrifugal subjectivity: the non-human possibility of being human, a posthumous subject conceptualized as a fluid and peripatetic flow that is wholly influenced by divergence. This is what can be expressed by the word “O-there”: someone who comes to being as a heterogeneous void which always is right there! This void, the “there”, is what supposed to be nowhere, nobody who owe its existence to the other. Here we can understand that why it is so crucial that subject sustains its otherness. For Cixous, “The other in all his or her forms gives me I. It is on the occasion of the other that I catch sight of me; or that I catch me at” (Cixous, 1997, 13). Defending the otherness, what for Cixous is everywhere and everything, despite possible differences that the singularity might be carrying, means prioritizing what is inconsistent with the oneself (a certain preferred meaning), what is seemingly awkward and inappropriate regarding the process of signification: this is some sort of depletion of all identities, as well as what Derrida, Cixous’s spiritual father, has in mind of femininity. Therefore, any attempt to providing a sort of topology for the feminine is doomed to failure. Because, in the same way that Cixous avoids defining the female writing, she rejects any determination of female situation by virtue of its displacement. Furthermore, as far as father or fatherland refers to the origins and ancestry, the female has no father, no roots and is like illegitimate child who only take on the mothering. Hence, the female, if acceded to the definition, will be limited and enter into the structure of male language. This is where the theory of feminine as the strangeness demonstrates its positive aspects. When we assume that the reality just occurs through the openness, that the commitment to the principles of any pretender regime ties and restricts us to the given limitations of a certain reading of the world, the most political action is nothing but releasing oneself from the stark borders and joining to the dead society of otherness. So, the phantom hiding in the rocks of femininity, should be transient in the margins of linguistic and semantic structures, and simultaneously retains his marginal self-destructive position in order to experience the reality differently every moment. The concept of the axis of indetermination aims to achieve a self-defeating situation, where the human subject can encounter with its own face, put oneself into danger so that to allow it’s other ones to appear: running the risk of “losing oneself”. Let’s recall that, “the subject must be risked. That is even what the subject is: by definition: risk. ‘At the risk of losing oneself. The risk is necessary’ … That is why the Cixousian subject does not stop running: it races against itself and against its narratives … the only safeguard for this subject so subject to, so much of a taken course, is to multiply the point of view, the points. The blind spots” (Sellers, 1994, 215- 216).

Conclusion

Cixous’s approach puts a fundamental philosophical assumption before us about the importance of de-perception and the female otherness. Where the masculine subjects and patriarchal systems tend to fix one way of understanding and calculation, Cixousian female subject tries to multiply the point of view for the numerous facts that may come into existence. Masculine fascist point of view acts like the natural perception: that is, it always keeps those parts of the world that fascinate him, while eliminates the unseen parts of reality. This mechanism leads to a one-dimensional worldview which stabilizes just one single perspective. In contrast, by pluralizing the point of view, by destructing the pivotal paradigm which is imposed by male thinking, the female allows the human perception to experience the infinite perspectives. This will be achieved due to the possibilities which the feminine provides for the world, the feminine which has such power only when it does not leave its marginal situation and does not lose its cognitive-perceptual pointlessness. A genuine encounter with the truth, happens through getting to the point of pointlessness. It seems that settling down at the heart of an ideology, or even any self-identification which, by definition, is confined to the presence in the monophonic symbolic dimension, does not allow running away from the borders or the emergence of polygonal experiences. For Cixous, the situation of being posthumous locates the female in the pre-ontological domain, before any existence, criteria and the perceptible objects. This is exactly what we can call the unnamable thing in the pre-symbolic world.

Original perception always occurs before the process of objectification, because by the perception of raw material as a ready-made object, human subject only recognizes the real rather than having the revisionist sighting. Conventional understanding can only detect the external objects by matching them with the mental categories and attributing them to the realities. Hence, the truth can only be understood by a stranger, a foreigner who meets the world for the first time. This requires an oscillation between self and the other, the seen and the unseen, that comes from the female, where it can go back and forth on the narrow border of perception without any settlement, the tribal, nomadic and transformative. The female whose libidinal energies are cosmic and unconscious, cannot tolerate and consent to the being-in-itself and stillness, because its existence always precedes its essence. The female is something like a pestilent move from itself to the other, from the stable to whatever stands outside the self, and so to a heaven for the stranger. The femininity distances us from death and returns us to the life, yet, the life is meant to keep moving, living a nomadic way of being means casting and setting the stage for the creation of new possibilities; Hence, life is nothing but a constant process of molting and marginality. Of course, this marginality again, does not imply any kind of exclusion of the women from equal rights in society, or excluding them at all. In contrast, it means that the femininity due to its relations with the other, can creates the new possibilities and new experiences for thinking, and this could occur, for Cixous, through the expression of feelings or its own identities.

Notes:

[1] . As she states, “when my family settled in Algiers, which was not their home town, … I felt my difference fiercely, my strangeness, and I had no co-conspirators in this strangeness [étrangeté]” (Cixous, 2008, 135).

[2] . Of course, this praise is two-way and reciprocal. As Cixous states, “Derridaeanized French language, he ransoms it, unmakes it, scours it, plays out its idiomatic potential, awakens the words buried under forgetfulness. He resuscitates it. When I heard him I found the liberty I needed: of course this liberty existed in Rimbaud, but with Jacques Derrida poetry began to gallop philosophy” (Cixous, 2008, 167).

[3] . The strategy of écriture feminine begun formally in the middle 1970s by Cixous, Irigaray, Kristeva, Catherine Clement, Chantal Chawaf, Monique Wittig, among others, and was focused on reading the literature in the bodily contexts of female experience.

[4] . In Coming to Writing and Other Essays, Cixous declares that “meditation needs no results. Meditation can have itself as an end, I mediate without words and on nothingness. What tangles my life is writing”. This means, in a sense, giving priority to writing over theory which reminds us that Derridaean strategy which she adopts to challenge the boundaries between theory and fiction.

[5] . “We go toward the most unknown and the best unknown, this is what we are looking for when we wrote. We go toward the best known unknown thing, where knowing and not knowing touch, where we will know what is unknown. Where we hope we will not be afraid of understanding the incomprehensible, facing invisible, hearing the inaudible, thinking the unthinkable, which is of course: thinking” (Cixous, 1993, 38).

[6] . In her works, Cixous has always been open to Heideggerean thoughts about language. As she says, “I have always read Heidegger with the utmost attention, because he is interested in writing” (Cixous, 2008, 148).

[7] . According to Lacan, the Law of the Father or the Name of the Father controls the subject’s desiring and govern the rules of communication and language by means of the work of Superego. For more information about this concept in Lacan see for example, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Evans, 1996).

[8] . Cixous is not, of course, the first writer who uses the combination of theory and fiction, or what we can call, novel-poetic-theory. A good example of this can be seen in the works of Georges Bataille.

[9] . An extraordinary example of this position can be found in Cixous’s short novel, The Day I Wasn’t There (2006) in which she uses her poetic unconsciousness language.

[10] . French sociologist and anthropologist who is well-known for his researches on diverse traditional rituals such as Potlatch (1872-1950). For more information about Mauss’s thoughts on gift, see for example, his famous book, The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies (1923).

[11] . As cixous declares, in psychoanalysis, as well as, philosophy, ethnology, and other discourses which deal with sexual difference, “I found nothing except the negative: tableau of a general repression” (Cixous, 2008, 59).

[12] . “Stepping ‘outside’, the narrator intends to let go of all sense of familiarity: ‘Cut yourself off absolutely. Become alien. Feel the other’s powerful presence inside you, stronger that you, and cease to be anyone but the other” (Cixous, cited in Sellers and Blyth, 2004, 44).

References:

Cixous, Helene. Three Steps in the Ladder of Writing. Columbia University Press. 1993.

Cixous, Helene. White Ink; interviews. Eds by Susan Sellers. Acumen, 2008.

Cixous, Helene. The Laugh of the Medusa, in Isabelle de Courtivon and Elaine Marks (eds), New French Feminism, Minneapolis: University of Massachusetts Press, 1981.

Cixous, Helene. Rootprints: Memory and Life Writing. Routledge. 1997.

Cixous, Helene, the Newly Born Woman. Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press. 1986.

Cixous, Helene, , The Laugh of the Medusa, trans by Keith Cohen, Paula Cohen, in Signs, Vol 1. No 4. (Summer 1976). 880.

Jacobus Lee, A. Barreca. Regina (eds). Helene Cixous: Critical Impressions. Gordon and Breach Publishers. 1999.

Julia Dobson. Helene Cixous and the Theater: the Scene of Writing. Peter Lang Publication. 2001.

Michel Woodward in Identity and Difference. Eds by, Kathryn Woodward. Open University. 2002.

Sellers, Susan; Blyth, Ian. Helene Cixous: Live theory. New York London: Continuum. 2004.

Susan Sellers, (eds). The Helene Cixous Reader, London and New York, Routledge. 1994.